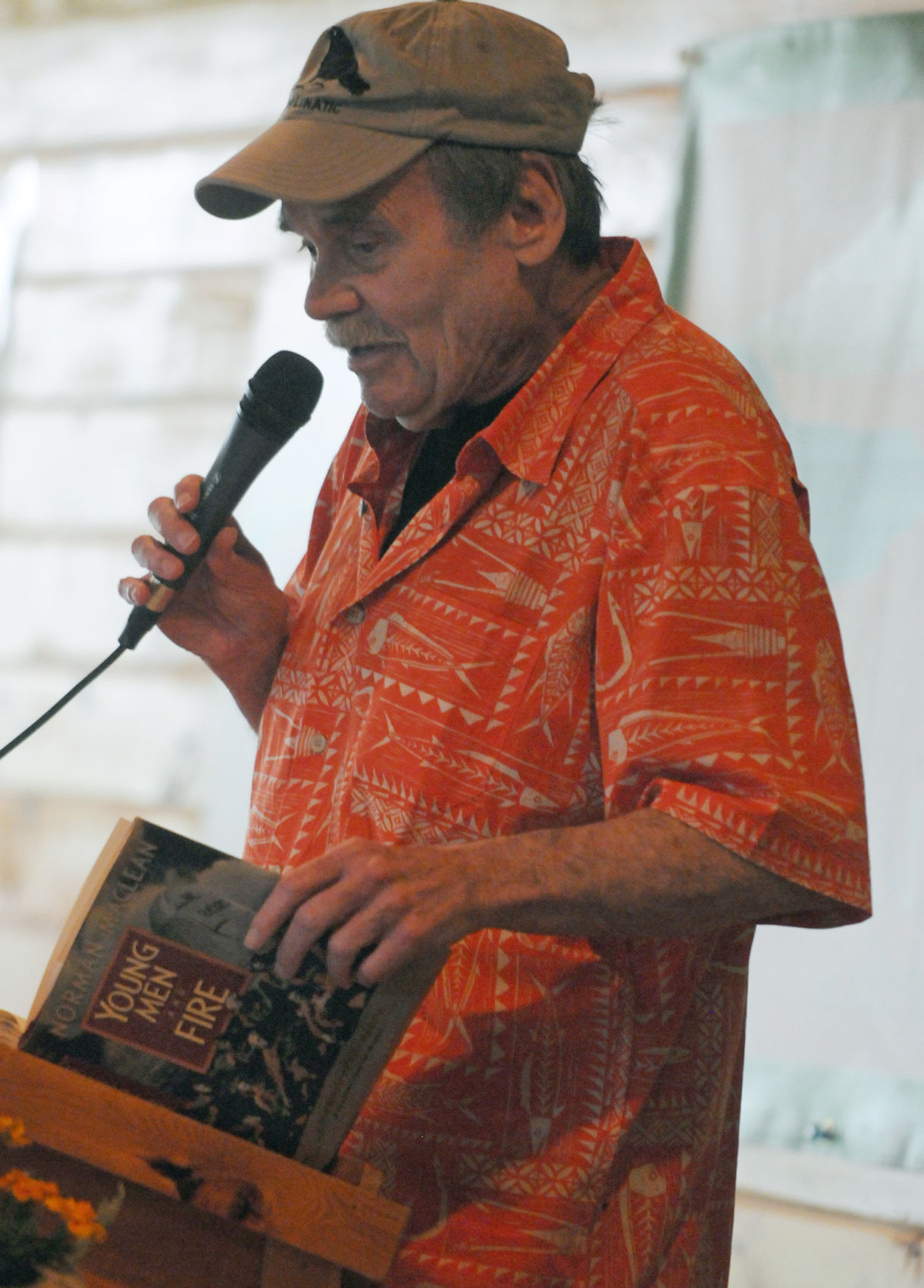

Only a life-long passion, which was posthumously published as Young Men and Fire in 1992, was to appear (Maclean died in 1990).

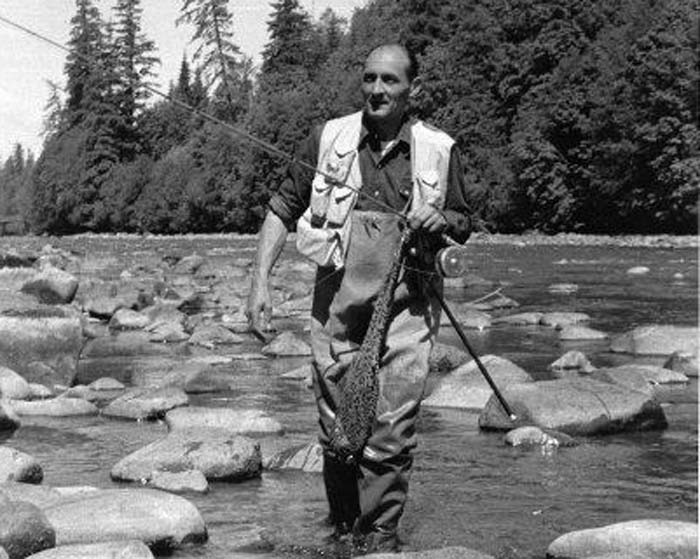

Chronic ill health, however, and an unflinchingly stubborn personal editorial exactitude limited his output. Clearly, he possessed a gift.Īnd then, after increasing critical acclaim and widespread success of A River Runs Through It, his followers patiently waited for more. Upon retirement in 1973, and after urging from his children and friends, he began crafting his stories from the distant past, partly as a challenge to himself to see if an aging, retired professor could pull it off, and partly as a testimony of his love for Montana. He returned each summer, however, to his native and beloved Montana and the family's cabin on Seeley Lake. We also learned that Maclean then left Montana in the 1920s, first for an Ivy League education, finally assuming a position in the English department at the University of Chicago where he flourished as an accomplished literary critic and as an inspiring professor of Shakespeare. This was a fellow who probably was very much acquainted with a Bitterroot valley prostitute who may very well have spoken in some variant of iambic pentameter (partially the subject of "USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky," the concluding story in A River Runs Through It). Yet as the reputation of the work gradually gained national traction and bits and pieces of his life emerged, we learned that indeed Norman Maclean had grown up in western Montana and he had worked for a time in 1910s in the Forest Service when both were in their youth, and yes, this soft-spoken English professor knew intimately the rawboned world of logging camps (the backdrop for the second story in A River Runs Through It) long before the din of chain saws and bulldozers intruded upon the forest solitude. There had to have been precursors decades earlier: short stories in this or that literary review or obscure journal or perhaps several lesser novels. Who was this writer? Why hadn't there been from him something before this? Surely someone of this talent had to have had an enormous literary corpus preceding this masterpiece. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs. On some of those rocks are timeless raindrops. The river was cut by the world's great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. Then in the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories and the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise. There are probably no more famous words in Montana letters than those of his closing: "Like many fly fishermen in western Montana where the summer days are almost Arctic in length, I often do not start fishing until the cool of the evening. Few who've read the trio of stories can forget the title novella's elegiac description of the Maclean family growing up in western Montana at the turn of the century, with the stern Scottish Presbyterian patriarch John Maclean's conflation of fly fishing with the spiritual rhythms of the Blackfoot River serving as backdrop to Norman's tragic and ultimately doomed attempt to save his younger brother, Paul, from himself. In 1976, after retiring from a distinguished career at the University of Chicago spanning nearly five decades, Maclean virtually singled-handedly put modern Montana literature on the map with his A River Runs Through it and Other Stories. In his spare, laconic style, Norman Maclean could describe beauty perhaps better, and certainly more economically, than any regional writer in recent memory.

The Norman Maclean Reader: Essays, Letters, and Other Writings by the Author of A River Runs Through ItĬhicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008īeautiful.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)